Big Data Organizations & Service Providers have weeks to get ready

The California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA)is going to be enforced starting on July 1, 2020 having gone into effect at the start of 2020 — and new guidance from the California Attorney General should quickly become the focus of any digital organizations with significant amounts of user data.

This blog post is not meant to be an all-encompassing summary of how to get ready for CCPA or the frameworks for sharing and selling user data — there are far too many complicated aspects, largely due to the fact that most organizations who are large enough to need to comply with CCPA, would also have European users and need to comply with GDPR, the European data privacy law.

There are several comments in the California Attorney General’s “Final Statement of Reasons” for CCPA that clarifies important rights and responsibilities under CCPA.

These details are being released at a time when COVID mobile tracking data has become the newest privacy outrage for users — and several aspects of the guidance reads as a direct rejection of the guidance issued by the online advertising and analytics industry groups NAI and IAB, who previously gave their members a blessing to share/sell COVID mobile tracking data to other businesses, researchers and the government to support the pandemic tracking efforts.

Both IAB and NAI encouraged members to share any data valuable against fighting COVID in the Senate hearing that was not on video, via their written statements for the hearing “Enlisting Big Data in the Fight Against Coronavirus.”

It’s clear that organizations who buy/sell/share user data, need to get much more serious about user consent, the categories of collection they undertake, and their potential legal exposure from not requesting user consent for a material change in collection purpose — and the CCPA guidance makes it clear that “simply putting up a new notice on a website after a consumer has already provided personal information, when that consumer may be unlikely to revisit the website (and even more unlikely to revisit the notice), is not meaningful consumer notice.”

If you are a business with significant user data (10+ million consumers in a calendar year), you don’t get to start every month coming up with new monetization strategies for your existing user data without getting permission from users to use their existing data for materially different efforts — and with the new categories of sources being clarified by the CA AG to now include: “Advertising Networks, Internet Service Providers, Data Analytics Providers, Operating Systems and Platforms, Social Networks, and Data Brokers” — things are about to get much more serious for organizations who have treated user consent like a blank check for future user data monetization efforts.

Brief disclaimer: I’m not a lawyer — i’m a longtime digital strategist who has a significant interest and experience with user data privacy frameworks (i’ve also got my CIPP/US privacy certification from the IAPP). I’ve been building and optimizing marketing and analytics stacks for 13+ years for politicians, businesses, my own startups, and client projects — with the last ~8 at my firm Victory Medium. I’m on Twitter @ thezedwards for any questions or feedback.

Excerpts from the Final Statement of Reasons from the California Attorney General’s Office, with Brief Comments on the Potential Scope / Impacts

The PDF for the Final Statement of Reasons can be viewed here. Additional links and CCPA resources can be found at the CA AG’s website.

Categories of data sources and the types of entities that collect data have been expanded to include and require more specificity, with several new entity definitions including, “ advertising networks, internet service providers, data analytics providers, operating systems and platforms, social networks, and data brokers.”

From page 1 of The Reasons:

Subsection (d) has been modified to provide further guidance and clarification for the definition of “categories of sources,” which is used throughout these regulations. (See Sections 999.301, subd. (q)(3), 999.308, subd. ©(1)(e), 999.313, subd. ©(10)(b).) “Categories of sources” has been clarified to mean “types or groupings of persons or entities” from which a business collects consumers’ personal information, not just “types of entities.” The definition has also been modified to require a business to describe its categories of sources “with enough particularity to provide consumers with a meaningful understanding of the type of person or entity.” The following examples have also been added to the definition: advertising networks, internet service providers, data analytics providers, operating systems and platforms, social networks, and data brokers.

A Business Can be Classified as Both a 1st and 3rd Party, Depending on the Context of the Collection

Much like under GDPR where an organization can act as both a Data Controller and Data Processor, CCPA now allows an organization to be categorized as both a 1st party and a 3rd party entity whom businesses share personal information, depending on the context of that collection:

Subsection (e) has been modified to provide further guidance and clarification for the definition of “categories of third parties,” which is used throughout these regulations. (See Sections 999.301, subd. (q)(5), 999.308, subd. ©(1)(g)(2), 999.313, subd. ©(10)(d).) “Categories of third parties” has been clarified to mean types “or groupings of third parties with whom the business shares” personal information, rather than “types of entities that do not collect personal information directly from consumers.” The definition has also been modified to require a business to describe its categories of third parties “with enough particularity to provide consumers with a meaningful understanding of the type of third party.”

These modifications are necessary because entities with whom businesses share personal information may also collect personal information directly from consumers in other contexts. The CCPA’s definition of “third party” excludes the business that collects personal information from consumers, meaning the business that collects a consumer’s personal information in a particular context; it does not exclude all businesses that collect personal information directly from consumers in any context. (Civ. Code, § 1798.140, subd. (w).) An entity may in some instances be the business that collects personal information from consumers and in other instances a third party that receives personal information collected by another business. Accordingly, the definition of “categories of third parties” has been modified to clarify this point. These modifications also provide more guidance to businesses concerning the information they are required to provide to consumers, especially when responding to a request to know. This additional guidance benefits consumers by requiring that businesses provide enough information for consumers to understand their data practices. By requiring businesses to describe categories of third parties in a manner that is easily understood by consumers, these modifications implement a performance-based approach. (See Schaub, Center for Plain Language.) It also benefits businesses, particularly smaller businesses that lack privacy resources, by clarifying the information they must provide to consumers.

Households get clarifications

Throughout CCPA and the guidance from the California Attorney General’s office, there are mentions of “households” — these are groupings of individuals, sometimes related to each other and other times just living together, who may have overlapping data or an interest in restricting access to their data from other members of the household.

Technically, a household oftentimes shares an IP address range between the members of the household, which can be used as a persistent identifier by advertising and analytics companies.

Household Data Access & Deletion requests are going to be challenging for some organizations, and several aspects of the CCPA guidance seems to be aimed at discouraging “Verification by IP Address” for Access/Deletion requests — and basically organizations need to not only account for household requests (group requests), but also come up with their own internal Trust & Safety solutions to reduce the likelihood of a household guest, Airbnb renter or some other temporary occupant taking advantage of an unsafe access/deletion process.

The CCPA guidance on pages 3–4 includes:

Subsection (k) was formerly subsection (h) and has been renumbered. The initial proposed definition of “household” has been modified to “a person or group of people who: (1) reside at the same address, (2) share a common device or the same service provided by a business, and (3) are identified by the business as sharing the same group account or unique identifier.” This change was made in response to comments that the initial proposed definition of “a person or group of people occupying a single dwelling” was overly broad. The change is necessary to ensure that the term does not encompass persons with only a transitory relationship to a dwelling or a tenuous connection to another resident. This change will benefit businesses by providing more guidance about which groups of persons to treat as a household and will benefit consumers by ensuring that those who only temporarily occupy a dwelling are not able to access or delete a consumer’s household information.

Offline data collection still requires notification before the “point at which” the business collects personal information

There are numerous sections of the CCPA guidance that attempt to provide guidance about when a consumer must be notified about the collection of personal information — and one important part of these regulations could basically implode the entire outdoor kiosk/POS mobileID tracking schemes here in California. Many of these outdoor scanners are basically constantly hovering up consumer data, and reselling it for everything from COVID tracking to Online-offline marketing attribution.

The CCPA regulations now require consumer notification at or before the “point at which” a business collects personal information from a consumer.

From page 4:

Subsection (l) was formerly subsection (i) and has been renumbered. The initial proposed definition of “notice at collection” required notice to be provided to consumers at or before the “time” of collection of personal information. The definition has been modified to state that the notice must be provided at or before the “point at which” a business collects personal information from a consumer. This change is necessary to make the definition consistent with the language used in the CCPA. (See Civ. Code, § 1798.100, subd. (b).) This change is also necessary to encompass both temporal proximity, such as in online data captures, and physical proximity, such as near a cash register at an in-store location where collection is taking place. This change will benefit businesses by providing further guidance on how to provide notice to consumers and will benefit consumers by making the notice more apparent when personal information is collected.

Guidance on Mobile Device Collections Raise Significant Questions for COVID Location Data Sales

The timing of when this CCPA guidance was written is important — these opinions were being written while massive amounts of mobile location data from the public was being bought, sold, and shared under the guise of consumer protection, and with the NAI and IAB advertising industry groups both blessing the practice of selling existing user mobile location data to support COVID tracking efforts.

What the CCPA guidance makes clear, and this should raise red flags for any organizations who took guidance from NAI and IAB on this issue and executed sales of existing user data, is that the CCPA guidance now makes it clear that organizations who provide SDK services to apps, and any app providing data for COVID tracking, need to provide a “‘just-in-time’ notice summarizing those categories of information that a consumer would not reasonably expect to be collected..”

Subsection (a)(4) was added to address instances in which a business collects personal information from a consumer’s mobile device for purposes that the consumer would not reasonably expect. In those instances, the business must provide a just-in-time notice summarizing those categories of information that a consumer would not reasonably expect to be collected and a link to the full notice at collection. The subsection also includes an example that illustrates this requirement and provides guidance as to what may be considered a purpose that a consumer would not reasonably expect. This subsection is necessary to provide transparency into business practices that defy consumers’ reasonable expectations, particularly when those uses are not reasonably related to an application’s basic functionality. The requirement benefits consumers by making notices more conspicuous in instances in which their personal information is being collected for purposes not reasonably expected. Subsection (a)(4) is consistent with the language, intent, and purpose of the CCPA to meaningfully give notice to consumers about what information is collected from and about them and to give them control over how businesses use this information. The CCPA provides the OAG with the authority to adopt regulations as necessary to further the purposes of the CCPA. (Civ. Code, § 1798.185, subd. (b)(2).) Inherent in this authority is the ability to adopt regulations that fill in details not specifically addressed by the CCPA, but fall within the scope of the CCPA. This just-in-time notice allows consumers to make an informed decision about how to interact with the business at or before the point of collection of their information, in furtherance of Civil Code § 1798.100, subdivision (b). The regulation also benefits businesses by providing clear guidance regarding when they must provide a just-in-time notice on a consumer’s mobile device.

The CCPA guidance goes on to further highlight mobile tracking situations that require unique disclosures, particularly any new use of consumer data that is “materially different than” the original purpose, writing:

Former subsection (a)(3) has been renumbered and is now subsection (a)(5). Subsection (a)(5) concerns restrictions on a business’s use of a consumer’s personal information for purposes other than those disclosed in the notice at collection. These restrictions are necessary because the consumer could have reasonably relied on the notice when interacting with the business and allowing it to collect their personal information. The subsection has been modified by changing “other than” to “materially different than.” This change was made in response to numerous comments urging that the restrictions be limited to uses that are “materially different” from those disclosed in the notice and is necessary to make the language of the regulation consistent with privacy best practices. For example, the FTC has long expected that companies should obtain affirmative express consent before using consumer data in a materially different manner than claimed when the data was collected. (See Fed. Trade Com., Protecting Consumer Privacy in an Era of Rapid Change: Recommendations for Businesses and Policymakers, (2012), p. viii, 57–58.) This change benefits businesses because businesses will not be required to inform consumers of immaterial changes. The change also benefits consumers by not overwhelming them with notices for every minor change, which may result in notice fatigue. The subsection also adds the term “previously collected.” This change is necessary to clarify that the subsection applies when a business seeks to use previously collected personal information for a use that is materially different than what was previously disclosed to the consumer, not for new personal information that it seeks to collect.

In light of the comments received from the public, the OAG further supplements its statement of reasons in support of subsection (a)(5) as follows. (See ISOR, pp. 8–9.) Subsection (a)(5) is consistent with the language, intent, and purpose of the CCPA to provide consumers with greater control over their information and meaningful ability to exercise their CCPA rights.

The CCPA guidance also includes an example scenario where businesses would be required to request consent for a new purpose:

When businesses change practices midstream, the consumer should have the opportunity to decide whether to agree to the new purpose. For example, a consumer may be comfortable allowing a business to collect their personal information to use in serving them advertisements for relevant products, but not if the business wants to use the information to conduct psychological experiments. Allowing consumers the opportunity to consent to this further use is consistent with the CCPA’s goal of fairness, choice, and control.

And it seems that some businesses were advocating to the California Attorney General that they should be able to merely update a notice / TOS / Privacy Policy, and that CCPA doesn’t provide the OAG authority to strengthen requirements and require consumer-consent for a new data collection purpose.

The AG’s guidance clearly shot down this argument, and the CCPA guidance seems to make it clear that a new purpose (like COVID location data sales using existing mobile data) would not be CCPA compliant and requires a business to request permission to use the existing data for the new purpose:

Some comments have interpreted Civil Code section 1798.100, subdivision (b), as only requiring an additional notice and prohibiting a consumer-consent requirement. The OAG disagrees with this interpretation. As already stated, the CCPA gives the OAG authority to promulgate regulations that further the purposes of the CCPA. Furthermore, requiring explicit consent puts the consumer in the same position they would have been had the material change been disclosed during the consumer’s first engagement with the business. It empowers the consumer to actively choose whether they want to maintain their relationship with the business. It is necessary to preserve the consumer’s ability to object to the use of their personal information for new purposes, particularly because the business already has their personal information. Without this requirement, businesses could be incentivized to minimize or delay any updated notice or to otherwise hinder a consumer’s ability to object to the new use. Thus, comments that propose simply updating an online privacy policy or providing notice without explicit consent for material changes to a business’s use of personal information would not serve the purpose of section 1798.100, subdivision (b). Such an approach would allow businesses to engage in passive notice updates without allowing consumers any agency to control how their personal information is used. Furthermore, simply putting up a new notice on a website after a consumer has already provided personal information, when that consumer may be unlikely to revisit the website (and even more unlikely to revisit the notice), is not meaningful consumer notice.

If you are an organization who has been using existing mobile location data from apps or SDKs and selling/sharing or using that data in any way to support COVID tracking efforts, that seems to be a significant CCPA violation without requesting permission from users for that new purpose.

Without a Posted Notice of Right to Opt-Out, Organizations Must Obtain Affirmative Authorization for the Sale of User Data

Additionally, in the CCPA Reasons, there is a rock-solid effort to remove loopholes that could allow a business to sell user data when the business didn’t have a posted notice of right to opt-out, unless the business “obtains the consumer;’s affirmative authorization for the sale.”

So for all the organizations that didn’t sell user data and didn’t have a posted notice of right to opt-out of data sales, they would be violating CCPA if they turned around and sold the user data without following back up with the consumer for their affirmative consent for the sale.

The CCPA Reasons from the CA AG also explicitly say why a business can’t just continue to update their data policy notices for new purposes or data sales, because as most people know about user behavior, people don’t go back to revisit privacy policy, terms of service, or data policy webpages, if they even review those pages once.

From page 15:

Subsection (e) was added to state that a business cannot sell personal information it collected during any time it did not have a notice of right to opt-out posted unless it obtains the consumer’s affirmative authorization for the sale. Because Civil Code section 1798.120, subdivision (b), requires a business that sells consumers’ personal information to third parties to provide consumers with notice of their right to opt-out of the sale of their personal information, the converse is also true: if the consumer has not been provided with notice of their right to opt-out when the business collected their personal information, the business cannot sell that consumer’s personal information. Subsection (e) is necessary to prevent a business from unilaterally and retroactively changing its policy to sell personal information that it collected during a time period when it expressly assured consumers that it did not sell such information. If a business decides to change their practice midstream, the business must obtain affirmative consent.

The OAG considered alternative ways to address this situation and determined that requiring businesses to obtain affirmative authorization is the most effective way to carry out the purpose and intent of the CCPA to give consumers notice and control, at the point of collection, over the sale of their personal information. While the alternative of allowing a subsequently posted notice of right to opt-out to apply retroactively would be less burdensome to businesses, it would not be as effective in informing the consumer of their right at the point of collection, when the consumer may be most aware of what personal information the business is collecting from them. Such an approach would allow businesses to engage in passive notice updates without allowing consumers any agency to control how their personal information is used, including when it was collected under false pretenses. Furthermore, simply putting up a new notice on a website after a consumer has already provided personal information, when that consumer may be unlikely to revisit the website (and even more unlikely to revisit the notice), is not meaningful consumer notice.

CCPA Restricts Service Providers from Retaining or Using Personal Information for Its Own Business Purposes — Direct Attack on COVID Tracking Data Acquired from SDK Companies , Called a “Substantial Modification” by the CA AG

There are several clarifications for Service Providers, and there seem to be additional restrictions and clarifications that will apply to any businesses that acquired user data as part of a Service Provider relationship — those businesses are not allowed to retain or use that personal information for its own business purposes.

Right now, there are a huge amount of analytics companies and mobile app SDK providers that acquired user data as part of Service Provider relationships with other mobile apps — and those organizations have been selling the data for COVID location tracking in violation of CCPA.

It seems that significant investigations and changes will need to occur based on these sections.

From page 32:

Subsection (C ) has been substantially modified. The subsection now prohibits a service provider from retaining, using, or disclosing personal information obtained in the course of providing services except to provide those services in compliance with the written contract for services and in four other limited circumstances. This prohibition is consistent with how the CCPA defines and regulates the disclosure of consumer personal information to service providers and service providers’ use of that information. For the purpose of processing personal information, the CCPA contemplates service providers to be an extension of the business for which it provides services. Civil Code section 1798.140, subdivision (v), defines a “service provider” as one who “processes information on behalf of [the] business” that provided the personal information, pursuant to a contract that prohibits “retaining, using, or disclosing the personal information for a commercial purpose other than providing the services specified in the contract.” Relatedly, a business does not “sell” personal information when it transfers that data to a service provider, provided that the service provider does not “collect, sell, or use the personal information of the consumer except as necessary to perform the business purpose” of the business that provided the personal information. (Civ. Code, § 1798.140, subd. (t)(2)©.) Thus, the intent of the CCPA is to prohibit a service provider from using personal information collected from one business for its own business purposes or to then provide services on behalf of a different business.

Many comments objected to the original text of subsection ©, claiming that the CCPA broadly authorizes service providers to retain and use personal information for any “business purpose.” But nothing in the CCPA allows a service provider to retain or use personal information for its own business purpose. Rather, as discussed above, services providers are expressly limited from retaining and using personal information. (Civil Code § 1798.140, subds. (v) and (t).) Indeed, the term “business purpose,” when used in the statutory text, contextualizes why a business discloses personal information to a service provider or third party, not the universe of possible ways a service provider could use that information. (See Civ. Code, §§ 1798.115, subd. (a), 1798.130, subd. (a)(4)©.) The CCPA requires that any disclosure of personal information from a business to a service provider be “necessary to perform a business purpose.” (Civ. Code, § 1798.140, subd. (t)(2)©.) Even in defining the term “service provider,” the CCPA makes clear that a business’s disclosure of personal information must be for a business purpose that is stated in the parties’ written contract. (Civ. Code, § 1798.140, subd. (v).) Subsection © thus accurately reflects the CCPA’s requirement that service providers act on behalf of a business by processing information to further the business’s specific business purpose and not for the service provider’s own business purposes.

CCPA Innovation & Other Notes from the Final Statement of Reasons from the California Attorney General’s Office

The California AG made it clear that the California Data Broker Registry was not only going to be essential for businesses to comply with who are in the business of buying or selling user data, but also pointed out that new industries and privacy innovation can be built with these registries via efforts to standardize global opt-out signals.

One section on Page 12 included these comments:

During preliminary rulemaking activities, the OAG learned that a consumer may not know who has and could be selling their personal information, given that the CCPA does not require businesses to disclose the specific persons or entities with whom they shared the consumer’s personal information. (Civ. Code, § 1798.110 [merely requires the disclosure of “categories of third parties” with whom a business shared personal information].) The data broker registry addresses this gap by publicly identifying specific businesses that may be selling the consumer’s personal information. Subsection (e) thus benefits consumers by allowing them to access, in one place, the information they need to exercise the right to opt-out of the sale of personal information from data brokers selling their personal information. It benefits businesses by reinforcing and streamlining their compliance with the data broker registry law and the CCPA. Subsection (e) also encourages the development of consumer tools or services by allowing innovators to pull information about how data brokers process requests to opt-out from a centralized repository.

Do Mobile Apps Need to Explain Data Sharing / Selling Before Download?

Mobile apps will be able to include a shorthand reference in their menu and provide links to read more about how the business collects personal information, instead of any required length or specific text.

But the organizations will still be required to provide details on their data collection on the download pages — basically before a user installs software, details on data collection/sales need to be accessible.

The reference to a “download page” in these CA AG Reasons could almost be interpreted to require disclosures on App Descriptions before someone installs an app — basically apps need to not only link to privacy policies, but also link to separate pages expressly on how that business collects or sells personal information under the CCPA frameworks.

From page 13:

Subsection (b)(1) has been modified to add that a business that collects personal information through a mobile application may provide a link to the notice within the application, such as through the application’s settings menu. This language was added in response to public comments seeking guidance on whether businesses could include this link through their mobile application’s settings menu. This modification is necessary to clarify that a business has discretion to provide a link directing consumers to the notice in lieu of including the actual language of the notice in the application’s settings menu. It benefits businesses by clarifying requirements for businesses and giving them the flexibility to shorten the language included in the actual application. This modification is not intended to speak to whether a business can provide the notice through its mobile application’s settings menu in lieu of providing it on the application’s download page. In the context of an online service, such as a mobile application, the CCPA defines “homepage” as “the application’s platform page or download page, a link within the application, such as from the application configuration, ‘About,’ ‘Information,’ or settings page, and any other location that allows consumers to review the notice . . . including, but not limited to, before downloading the application.” (Civ. Code, § 1798.140, subd. (l) (emphasis added).) This requires that the business provide the required information on both the download page and within the application itself, such as through the application’s setting page.

Offline customer interactions getting online notices

Under the CCPA guidance, businesses that “substantially interacts with consumers offline may satisfy the requirement that it use an offline method to provide notice to consumers by posting signage directing consumers to ‘where the notice can be found online.’”

This full section seems to indicate that at some point in the future, there will be more webpages that are known and that explain how various Point of Sale kiosks, digital billboards and other pedestrian tracking technology is sharing and selling user data. This Reason seems to be another section that will eventually encourage innovation and new privacy products.

From page 14:

Subsection (b)(2) has been modified to clarify that a business that substantially interacts with consumers offline may satisfy the requirement that it use an offline method to provide notice to consumers by posting signage directing consumers to “where the notice can be found online.” This modification was made for the same reasons the change was made in section 999.305, subsection (a)(3)©, above. The modification is necessary to align this provision with section 999.305, subsections (a)(3)©, (b)(3), and (b)(4).

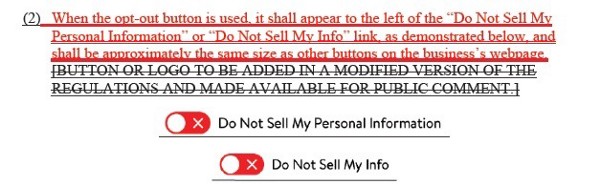

Everyone hated the “Do Not Sell” Button, AG Agrees

In what is potentially the shortest Reason amongst the CCPA guidance from the California Attorney General, there is a short mention of the ill-fated “opt-out button of shame” that was suggested in previous documents from the AG’s office and quickly reduced to ash by UI/UX experts across the internet.

From page 15:

Former subsection (f), regarding the proposed opt-out button, has been deleted in response to the various comments received during the public comment period. The OAG has removed this subsection in order to further develop and evaluate a uniform opt-out logo or button for use by all businesses to promote consumer awareness of how to easily opt-out of the sale of personal information.

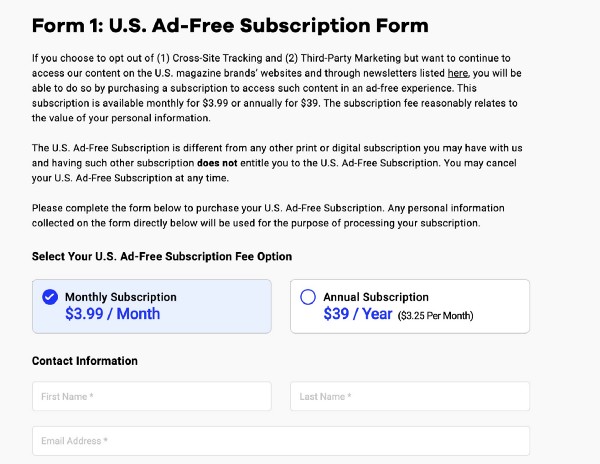

Discounts for Sharing / Selling Data, New Ad-Free Subscriptions

There are several sections in the CCPA Reasons about providing discounts to consumers for their data.

I’m not going to excerpt these sections because it’s going to be very hard to thread this needle without violating CCPA, and i’ll need to spend more time on these sections before providing any guidance or opinions about the impacts on various discounting strategies.

There are some businesses across the United States experimenting with this, and some may have a higher risk tolerance, be simply testing the waters, or be looking to aggressively move into these ad-free markets.

But one thing is clear, if you’re trying to provide discounts to consumers for ad-free experiences or to sell their data, you should read those sections and consult an Attorney to help you craft the right pricing options and disclosures.

Good Clarity: If you don’t sell data, you don’t need to provide a “notice of right to opt-out”

Several sections in the CCPA Reasons helped to clarify that businesses would not need to provide a notice of right to opt-out of data sales, if that business doesn’t sell data.

It’s likely that many businesses complained that this messaging would give consumers the wrong impression about a business, so this section helps to clarify that CCPA is going to be flexible enough in deployment to not provide false signals of data sales.

From page 21:

Section 999.306, subsection (d), also provides that a business that does not sell personal information does not need to provide a notice of right to opt-out if it states so in its privacy policy. Thus, the modifications make the language of the regulation consistent with the language in the CCPA and harmonize this subsection with section 999.306, subsection (d). These modifications benefit businesses and consumers by providing clarity and transparency about businesses’ baseline obligations: businesses that state that they sell personal information must post a notice of right to opt-out, and businesses that do not sell personal information will affirmatively state so.

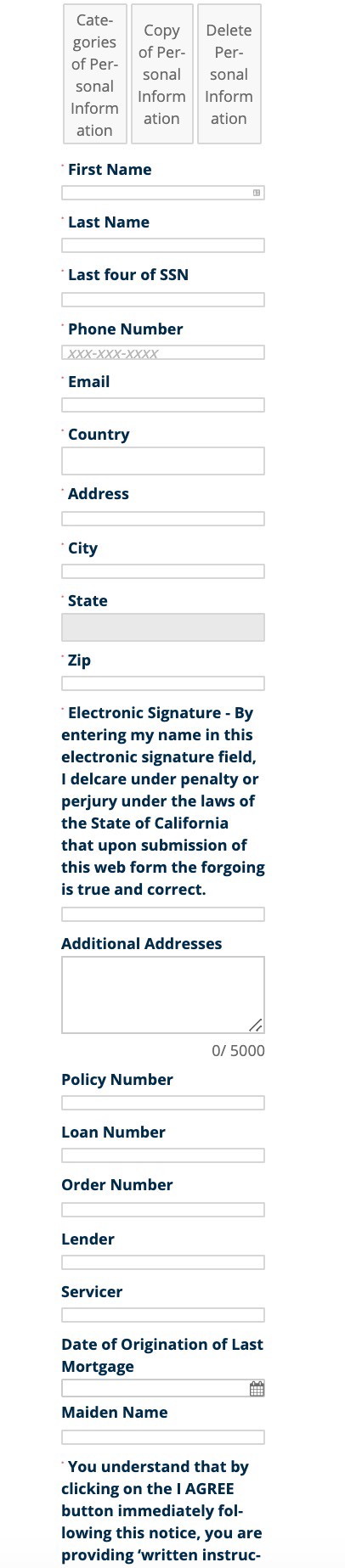

Businesses Urged to Make a “Fact-Specific Determination of What Process to Use” for Consumer Requests to Know/Delete, Only Email Required

There are numerous organizations like Mortgage brokers, Banks and Insurance companies that are building complex processes for consumers to safely request to know/access / delete their data.

For many of these organizations, there were concerns about restrictions being placed on their online forms — but it seems that a business will not be limited by the fields they request from people or authorized agents to complete the submissions.

The CCPA Reasons also provide some clarity for organizations that operate primarily offline and some assurances to consumers that the primary method they engage with a business needs to have a way to for them to utilize their rights.

From pages 21–22:

Subsection (a), which governs the methods a business must provide for the submission of consumers’ requests to know, has been modified to provide that businesses operating exclusively online and that have a direct relationship with a consumer from whom it collects personal information shall only be required to provide an email address for submitting requests to know. The requirement that businesses operating a website must provide an interactive webform has also been deleted. ..

Subsection (c ), which requires a business to consider the methods by which it interacts with consumers when determining which methods to provide for submitting requests to know and requests to delete, has been modified in four ways. First, the word “primarily” has been inserted before “interacts” to clarify the meaning of the subsection. This clarification is necessary to prevent businesses from designating obscure methods for the submission of consumer requests as a way of discouraging consumers from exercising their rights under the CCPA. Second, the sentence “At least one method offered shall reflect the manner in which the business primarily interacts with the consumer, even if it requires a business to offer three methods for submitting requests to know” has been deleted. This change is necessary so that the language used in the regulation is consistent with the language used in the CCPA. (See Civ. Code, § 1798.130, subd. (a)(1)(A)-(B).) Third, language has been added requiring businesses that primarily interact with consumers in person to consider providing an in-person method for submitting requests. The regulation provides a few examples of in-person methods: a printed form the consumer can directly submit or send by mail, a tablet or computer portal that allows the consumer to complete and submit and online form, and a telephone by which the consumer can call the business’s toll-free number. These examples provide guidance on how businesses should determine which methods to make available to consumers, including those discussed in Civil Code section 1798.130, subdivision (a)(1), while addressing situations in which consumers may need direct, in-person assistance in exercising their CCPA rights. This regulation is necessary to prevent businesses from designating obscure methods for the submission of consumer requests as a way of discouraging consumers from exercising their rights under the CCPA, while also providing businesses with flexibility to adopt methods that are compatible with their business practices. …

Businesses need to help consumers with CCPA requests, remedy deficiencies in submissions

Businesses should create templates for customer support, and are required to provide assistance to consumers who may be unaware of the businesses’ “designated method for submitting CCPA requests.”

From page 23:

Consistent with this legislative intent, the regulation provides guidance for instances in which a consumer’s attempt to exercise their CCPA rights is not submitted through a business’s designated methods or is deficient for a reason unrelated to the verification process. Businesses should provide assistance to consumers who may be unaware of the business’s designated method for submitting CCPA requests or may have made a mistake by contacting the business via some other method. Furthermore, based on the OAG’s technical expertise in this area and understanding of business practices, treating a consumer’s request as properly received or informing the consumer of the proper method of request is not unduly burdensome. If the business treats a request as properly received, the request proceeds through its designated CCPA-request process. If the business declines to do so, the business can simply provide the consumer with a pre-formulated response with information on how to submit the request and remedy deficiencies.

Businesses Should Reply Within 10 Business Days to Requests to Know / Delete, Have 3 Months to Comply

A business should test their own processes on a regular basis — if an organization fails to acknowledge receipt of a Request to Know / Delete within 10 business days, or fails to provide additional details within the first 45 day window, or the 45-day optional extension, that business is potentially in violation of CCPA.

There are several significant sections on the appropriate way to respond to requests, and how quickly these need to be done. The significant details in these sections should remove any doubt that these timing windows are essential for businesses to comply with CCPA.

From pages 23 and 24:

Subsection (a) has been modified in three ways. First, it has been modified to specify that the time period to confirm receipt of a request is 10 “business” days. This change was made in response to public comments seeking clarification of whether the initial proposed “10 days” constituted calendar days and expressing concern that 10 days was not enough time for a business to confirm receipt, particularly when received during business holidays. The clarification of “business days” addresses business holidays and lessens the burden on businesses. Second, the phrase “in general” has been added to clarify that a business’s confirmation of receipt of request simply needs to provide a general description of the business’s verification process. This change was made in response to public comments that requested guidance regarding the level of detail required and that expressed concerns that specific descriptions of a business’s verification process would reveal information to bad actors that could be used to evade security procedures. This modification balances the CCPA’s intent to provide rights and transparency to consumers with the burden on businesses, including potential security concerns. (Civ. Code, §§ 1798.185, subd. (a)(7), 1798.185, subd. (b)(2).) Third, two sentences have been added to clarify that confirmation of the receipt of a request may be made in the same manner in which the request was received, for example by phone. This change was made in response to public comments and is necessary to provide businesses guidance regarding how to confirm receipt of requests. It also reduces the burden on businesses by streamlining the communication methods for receiving and confirming receipt of requests.

Subsection (b) has been modified in two ways. First, the word “calendar” has been added to clarify that the time period to respond to requests to know and requests to delete is 45 calendar days. This change was made in response to comments that sought clarification on whether the time period was calendar or business days. Consumers exercising their rights to make requests under the CCPA should not be hindered by unreasonable delays, and 45 calendar days provides businesses with sufficient time to provide the required response, especially considering that they can extend the time to respond by another 45 calendar days. This change is necessary to avoid possible confusion about how to calculate the 45-day requirement. This modification ensures that businesses expediently address consumer requests and prevents excessive wait times for responses.

Requests to Know and Delete Must be Verified, Requests to Opt-Out Don’t Require Verification — 15 Day, 90 Day Requirements for Opt-Out Compliance

Most organizations provide an “opt-out” through simple immediate mechanisms, but if an organization is working with 3rd parties to sell consumer information, then a series of very important deadlines are triggered when a consumer requests to opt-out of this process.

The CCPA Reasons includes several details on these deadlines and responsibilities, from page 39:

Former subsection (e) has been renumbered and combined with subsection (f). Subsection (f) now states that a business shall “comply” with a request to opt-out as soon as feasibly possible but no later than 15 “business” days from the date the business receives the request. It also no longer requires a business to notify all third parties to whom it sold the consumer’s personal information within 90 days prior to its receipt of the opt-out request, or to direct those third parties not to sell the consumer’s information. Instead, it requires a business that sells a consumer’s personal information to any third parties after the consumer submits their request but before the business complies with that request to notify those third parties that the consumer has exercised their right to opt-out and to direct those third parties not to sell that consumer’s information.

The modification that a business comply with the request within 15 business days was made after considering public comments from many businesses and consumer advocates. Some comments called for eliminating the 15-day requirement or extending it to align with the 45-day requirement for responding to requests to know or to delete. Some comments claimed operational difficulties in complying with opt-out requests within 15 days, particularly if requests are received during the holidays, and asked that the regulation at least be modified to 15 business days, not calendar days. Other comments advocated for requiring compliance “immediately” or within 24 hours of receipt of the request due to the immediate nature of the collection and sale of personal information online. The OAG weighed these various comments and determined that 15 business days appropriately balances the right of consumers to opt out at any time with the burden on businesses to process opt-out requests.

Significant Clarification of CCPA Definition of Data Sale” Includes “Any Commercial Purpose”

In what is potentially one of the more important sections of the CCPA Reasons, the California Attorney General makes it clear that if a business uses consumer data for “any commercial purpose” there will be a “general fairness principle to ensure that a business that is not able or willing to disclose personal information to the consumer cannot profit or commercially benefit from that personal information.”

This section of the Reasons will need more clarification but I’ve been waiting for some part of the CCPA guidance that could apply to how some businesses upload additional User Data to Google Analytics, and associate that data with UserIDs shared between the business and Google — these match tables are used to improve an understanding of marketing funnels, KPIs, and profitability — and are certainly for a “commercial purpose” and provide valuable new data and context for both the business and Google.

I’ve tweeted about this niche issue here and I believe that organizations will need to disclose to users that they are sharing data with Google (and this could apply to other situations of data sharing), and organizations doing this will potentially need to provide the details to users in CCPA Requests to Know.

From page 26:

Subsection ©(3)©, which requires that the business not sell the personal information or use it for any commercial purpose, applies a general fairness principle to ensure that a business that is not able or willing to disclose personal information to the consumer cannot profit or commercially benefit from that personal information. Finally, subsection ©(3)(d), which requires the business to describe to the consumer the categories of records that may contain personal information that it did not search, is necessary to provide transparency to consumers. It informs the consumer that the business may have other personal information about them but assures them that this information is only maintained by the business in an unsearchable or inaccessible format, solely for legal or compliance purposes, and is not being used for the business’s commercial benefit.

Although some public comments suggested modifying the regulation to permit businesses to fall within this exception if any (rather than all) of these subsections apply, such a modification would too easily allow a business to evade its obligations under the CCPA and could incentivize behavior that would undermine a consumer’s ability to exercise their CCPA rights and access what personal information the business has collected about them.

Biometric FaceID Technical Data Not Required to be Disclosed in Requests to Know, Businesses Must Still Acknowledge They Have the Data

While not surprising, the CCPA provided guidance that would be useful for companies like Apple and Google that have growing biometric security face scans used to open phones and other devices — those businesses will not be required to disclose this technical data in a response to a request to know, but must acknowledge they have the data.

From page 26:

Second, subsection (C )(4) has been modified to add “unique biometric data generated from measurements or technical analysis of human characteristics” to the list of specific pieces of personal information that a business shall not disclose in response to a request to know. This change is necessary to balance a consumer’s right to know with the harms that can result from the unauthorized disclosure of information….Third, subsection (C ) (4) has been modified to require a business to inform consumers with sufficient particularity that it has collected the type of information set forth in the regulation. It also includes a clarifying example. This change is necessary because it provides direction to businesses on what to communicate to consumers when they are prohibited from disclosing these specified pieces of personal information. It benefits consumers by providing them with information to make privacy decisions while protecting them from the harms that could result from the unauthorized disclosure of this sensitive personal information.

There could be a Cold Storage Right to Delete Loophole That Keeps Some Requests in Limbo

There’s an important balance between reducing consumer rights and ensuring businesses aren’t overly burdened — the current CCPA guidance seems to provide a loophole for businesses that can’t access an archived or backup system to delete user data. When the archival system is eventually accessed, the business is supposed to then trigger deletion requests that were submitted between the last access point.

There are potentially scenarios where a business tries to reduce CCPA compliance costs by offloading certain customers (maybe product returns?) into a cold storage location and only accessing it once a year to batch delete any customer requests. It’s probably appropriate to leave this loophole and wait for a business to abuse it, due to this probably being an underused loophole.

From page 28:

Subsection (d)(3) has been modified to allow a business to delay compliance with the consumer’s request to delete only with respect to personal information stored on an archived or backup system until the archived or backup system “relating to that data is restored to an active system or next accessed or used for a sale, disclosure, or commercial purpose.” This change was made in response to comments that were concerned that the initial proposed language “next accessed or used” would be burdensome because the next access or use may be for reasons unrelated to the consumer’s personal information, and that it would deter businesses from implementing reasonable data security practices and procedures because routine maintenance, general testing, or testing of disaster recovery protocols could trigger a deletion obligation. The comments also contended that many archived or backup systems do not allow specific, targeted deletions, and thus it would not be technically feasible to delete a particular consumer’s information when the archive or backup system was accessed or used. By modifying the regulation to limit the compliance obligation for deleting personal information on backup systems to when those systems are restored or used for a sale, disclosure, or commercial purpose, the regulation lessens the burden on businesses. The modification also preserves the consumer’s right to delete when the business discloses or commercially benefits from access or use.

Problematic Privacy Issue: Lists of “Consumers Who Used CCPA Rights” Allowed and Required for 24 Months, Broadly-Defined Suppression Lists

One of the worst opinions in the CCPA Reasons, that will potentially lead to very long and invasive forms for Requests to Know/Delete, allows a business to create a global suppression list and “requires a business to maintain records of consumer requests and how the business responded for 24 months” and that the business “may retain a record of the request for the purpose of ensuring that the consumer’s personal information remains deleted from the business’s records.”

Another way to put this, a business can let you Request to Delete your data, and require that you submit pieces of information to confirm your identity that the business *did not have before you submitted the form* and then the business can hold that information for 24 months. At any point in the future, if the consumer reactivates their account, there doesn’t seem to be an explicit ban on a business merging all customer data, including the data submitted on the Right to Know / Delete forms, into the larger customer account/records.

I believe the California Attorney General’s office, if they haven‘t already, should clarify to businesses that users should be provided with choice (or businesses flat banned) from merging the data submitted in a Right to Know/Delete into larger customer data profiles, at least without user consent. CCPA should not be used to append new data to customer records, and attempts to do that should only be possible with strong communication to users about that process.

From page 29:

Subsection (d)(5) has been modified in three ways. First, the regulation now correctly cites to “section 999.317, subsection (b),” which requires a business to maintain records of consumer requests and how the business responded for 24 months. Second, subsection (d)(5) has been modified to clarify that the business only needs to inform the consumer of the record-keeping requirement if it complies with the request. Although the record-keeping requirement in section 999.317, subsection (b), applies to all requests received, including those the business denies, the disclosure to the consumer required here is necessary to dispel any assumption that granting a request to delete will also delete any record of the request. Notification that the request was denied is unlikely to lead to such an assumption. Third, language has been added to clarify that a business may retain a record of the request for the purpose of ensuring that the consumer’s personal information remains deleted from the business’s records. This change was in response to comments seeking guidance on whether businesses can maintain a suppression list. This change benefits businesses by dispelling uncertainty and benefits consumers by preventing a business from re-collecting information that the consumer had previously requested it to delete.

Service Providers for Public (Government) and Nonprofit Entities Given Disclosure / Deletion Exemptions, Potentially a Loophole for Government Data Brokers

This is probably a good but overly broad opinion — it feels like a potential loophole for massive data collection companies that are partnering with governments, and building profiles on ordinary Americans.

These sections were probably important to include, but these Service Provider exemptions for businesses working with Public and Nonprofit entities will need to parsed, and potentially certain Government Data Brokers not given this same blanket exemption.

From page 30:

In light of comments received from the public, the OAG further supplements its statement of reasons in support of subsection (a). (See ISOR, p. 21.) Overall, subsection (a) is necessary to address the unintended consequences that would result from allowing consumers to access and delete personal information held on behalf of public and nonprofit entities and that would otherwise not be subject to the CCPA. Like businesses, public and nonprofit entities outsource operational needs through service providers that essentially perform tasks as if the public or nonprofit entity was doing the task in-house themselves. These public and nonprofit entities also store documents in cloud storage, use email systems provided by third parties, and employ vendors to manage data. For example, a public school district may use a service provider to secure student information, including each student’s grades and disciplinary record. Without this regulation, service providers used by public and nonprofit entities may be required to disclose or delete records in response to consumer requests because they may constitute businesses that maintain consumers’ personal information. Service providers for public and nonprofit entities could also be asked to disclose personal information maintained by a government agency, despite the fact that such files may be expressly exempt from disclosure under the Public Records Act.

Accordingly, the OAG has promulgated this regulation pursuant to its authority to adopt regulations as necessary to further the purposes of the CCPA. (See Civ. Code, § 1798.185, subd. (b)(2).) Treating a service provider for a public entity or nonprofit as a “business” would not support the purpose and intent of the CCPA because it may expose otherwise exempt personal information to access and deletion requests or force service providers to create unnecessary and burdensome systems to respond to consumer requests. California law does not provide a right to delete information held by a public entity, nor does it provide a right to access personal information held by a nonprofit entity. The CCPA imposes obligations on “businesses,” which excludes public and nonprofit entities. (See Civ. Code, §§ 1798.100, 1798.105, 1798.110, 1798.115, 1798.120 [imposing obligations on businesses].) It is not intended to allow consumers to know or delete personal information collected by a non-business merely because the non-business outsources tasks to a service provider. In addition, California law already imposes a separate and distinct legal regime to access information held by public entities, including requirements and exceptions that differ from the CCPA. (See, e.g., Gov. Code, § 6250 et seq.) Without this regulation’s clarification, non-businesses, such as public and nonprofit entities, may not be able to employ service providers without risking disclosure or deletion of personal information or without unnecessary and burdensome costs, which may cause them to incur extra expenses to perform operations internally.

Opt Out Signals for the Sale of Personal Information Urged to Include Global Signals, New Innovation Needed

There is a long history of browsers, publishers, and advertising companies trying to agree on global opt-out signals, and CCPA urges this process to continue and for consensus to be made so that consumers can opt-out via global privacy controls.

The requirements included in this CCPA guidance are minimal, but the sections are interesting and should be read by anyone working with Consent Management Platforms.

From pages 36–38:

Subsection (d)(1) has been added to provide clear guidance that any privacy control designed or developed should clearly communicate or signal that a consumer intends to opt-out of the sale of personal information. This subsection addresses public comments concerned that a global privacy control may not respect consumer choice, as well as comments seeking clarification on what would constitute a privacy control that communicates the consumer’s choice to opt-out. By requiring that a privacy control be designed to clearly communicate or signal that the consumer intends to opt-out of the sale of personal information, the regulation sets clear parameters for what the control must communicate so as to avoid any ambiguous signals. It does not prescribe a particular mechanism or technology; rather, it is technology-neutral to support innovation in privacy services to facilitate consumers’ exercise of their right to opt-out. The regulation benefits both businesses and innovators who will develop such controls by providing guidance on the parameters of what must be communicated. And because the regulation mandates that the privacy control clearly communicate that the consumer intends to opt-out of the sale of personal information, the consumer’s use of the control is sufficient to demonstrate that they are choosing to exercise their CCPA right.

Subsection (d)(2) has been added to clarify how a business must respond when receiving a global privacy control signal for a consumer who has previously agreed to allow the sale of their information, including through participating in a financial incentive program or through a previous business-specific setting. The subsection requires the business to respect the global privacy control signal, but allows the business to notify the consumer of the conflict and ask the consumer to confirm their business-specific privacy setting or participation in the financial incentive program. This subsection is necessary to eliminate confusion by businesses that have received conflicting manifestations of intent from a consumer. It also provides businesses guidance on how to interpret Civil Code section 1798.135, subdivision (a)(5)’s 12-month prohibition on requesting that the consumer authorize the sale of their personal information for consumers who have enabled a global privacy control. Furthermore, this modification benefits consumers by ensuring that they can make discrete choices about the sale of their personal information while still enjoying the ease and reduced friction of not having to submit separate requests to opt-out on multiple websites or applications.

In light of the comments received from the public, the OAG further supplements its statement of reasons in support of subsection (d) as follows. (See ISOR, p. 24.) Subsection (d) requires a business that collects personal information online to treat user-enabled global privacy controls as a valid request to opt-out. This subsection is forward-looking and intended to encourage innovation and the development of technological solutions to facilitate and govern the submission of requests to opt-out. Given the ease and frequency by which personal information is collected and sold when a consumer visits a website, consumers should have a similarly easy ability to request to opt-out globally. This regulation offers consumers a global choice to opt-out of the sale of personal information, as opposed to going website by website to make individual requests with each business each time they use a new browser or a new device.

As stated in the ISOR, this subsection is necessary because without it, businesses are likely to reject or ignore tools that empower consumers to effectuate their opt-out right. This is based on the OAG’s expertise in this subject area. As the primary enforcer of the California Online Privacy Protection Act (Bus. & Prof. Code, § 22575 et seq.) (CalOPPA), the OAG has reviewed numerous privacy policies for compliance with CalOPPA, which requires the operator of an online service to disclose, among other things, how it responds to “Do Not Track” signals or other mechanisms that provide consumers the ability to exercise choice regarding the collection of personally identifiable information about their online activities over time and across third-party websites or online services. (Bus. & Prof. Code, § 22757, subd. (b)(5).) The majority of businesses disclose that they do not comply with those signals, meaning that they do not respond to any mechanism that provides consumers with the ability to exercise choice over how their information is collected. Accordingly, the OAG has concluded that businesses will very likely similarly ignore or reject a global privacy control if the regulation permits discretionary compliance. The regulation is thus necessary to prevent businesses from subverting or ignoring consumer tools related to their CCPA rights and, specifically, the exercise of the consumer’s right to opt-out of the sale of personal information.

The end, but not all the highlights

There are several dozen niche issues throughout CCPA and the Final Statement of Reasons that were not discussed in this already, massive blog post.

The purpose of this post was to flag some important sections that need to be reviewed by digital strategists, Data Protection Officers, and lawyers working with big data, and flag a few issues that deserve more debate.

Do you have feedback or think I missed the mark on something? Feel free to respond to the post below or drop me a note on twitter @ thezedwards

Recent Comments